1-College of Veterinary Medicine, Western University, Pomona, CA 91766-184, USA.

2-Anatomfa y Embriolog{a, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad de Murcia, Campus de Espinardo, 30071 Murcia. Spain.

3-Department of Comparative Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, 2407 River Drive, Knoxville, TN, 37996, USA.

4-Departmento Anatomfa Veterinaria. Universidad Nacional de Aguas Calientes, Mexico.

Numerous silicone impregnated specimens were produced for many years to increase our specimen inventory. Six current methods of silicone plastination were used with the intent to evaluate the resultant products. These included the classic von Hagens' (SI0, German, BiodurTM) cold method and five modifications of this method: Chinese, Corcoran, VisDoctaTM, North Carolina A and B. All of these methodologies use polymer, catalyst, chain extender, and cross-linker which are commonly used in today's silicone polymer industry. Cold acetone was used on most specimens; however, room temperature acetone was used on some specimens. The classic impregnation process, using decreasing pressure, was utilized in each process to exchange the intermediary solvent (acetone) with the polymer. The difference in these techniques was primarily the number of reactants and how they were combined and utilized in the plastination process. Specimens produced by the classic SI O method (using an impregnation reaction-mixture of polymer, catalyst and chain extender, with later cross-linking) and similar copies of this process (VisDocta1M, North Carolina A) routinely yielded exquisite surface detail of the specimen. Combining the cross-linker and polymer as the impregnation reaction-mixture with later catalyst application (Corcoran) produced specimens with a granular semi translucent surface. The impregnation-bath consisting of polymer alone (China, NC B) yielded good surface detail but occasionally yielded specimens with small, dry semi translucent areas on the surface if catalyst and/or cross-linker were added. However, all specimens produced by all methods were deemed useful. The combination of ingredients is the key factor in the differing results.

plastination; silicone; polymer; evaluation; surface; detail

R. W. Henry: Telephone: 865 - 974 - 5822; Fax: 865 - 974 - 5640; E-mail: rhenry@utk.edu

![]()

The plastination process for impregnation of biological tissues has remained nearly the same since its inception twenty-seven years ago by von Hagens (von Hagens, 1979a, 1979b, 1980, 1981, 1985; Bickley et al..1981, 1987; Tiedemann and von Hagens, 1982; Henry.1987, 1995, 1998; Oostrom, 1987b; von Hagens et al. 1987; Nicaise et al., 1990; Henry and Nel, 1993; Weiglein and Henry, 1996; von Hagens and Whalley, 2000). The various polymers, catalysts, chain extenders and cross-linkers used for plastination are all products currently used in the silicone polymer industry (Holladay et al., 2001; Henry et al., 2002b; Henry, 2004). There are at least six methodologies widely used today: SI0 (von Hagens', Biodur™), Corcoran (Dow), Chinese (Su-Yi), YisDocta™ (Italy), North Carolina A (NC A) and B (NC B). The major difference in these processes is how the components are combined and used during the process. Combination of polymer and catalyst (S 10, YisDocta™, NC A) yields an unstable impregnation reaction-mixture which may be semi stabilized and hence the rate of thickening (chain elongation) remarkably retarded if the reaction-mixture is stored at -20"C or less. Impregnation is recommended at - 15°C but may be carried out at slightly lower or much higher temperatures. However, the combination of polymer and cross-linker (Corcoran) yields a stable impregnation reaction-mixture even at room temperature and hence impregnation with such a product is routinely done at room temperature (Glover et al., 1998; Henry et al., 2001; Latorre et al., 2001; Raoof. 2001). Generally, China and NC B use only the polymer for impregnation (a stable impregnation bath at room temperature) and later a catalyst/cross-linker may be added. However, on hairy specimens it is desirable to use no additives. Any of these combinations have been recognized to produce useful, durable specimens (von Hagens 1979a, 1979b, 1980, 1981a, 1982, 1985; Bickley et al., 1981, 1987; Tiedemann and von Hagens, 1982; von Hagens et al., 1987; Weiglein, 1996; Zheng et al., 1996, 1998b, 2001; Glover et al., 1998; Henry, 1998: von Hagens and Whalley, 2000; Henry et al., 2002a, 2004; Latorre et al., 2002). However, it has been noted that surface clarity appears altered in specimens produced using cross-linker and polymer as the impregnation-mixture (Henry et al., 2001; Latorre et al., 2001; Henry, 2004). However, surface clarity is altered in specimens produced using cross-linker and polymer as the impregnation-mixture (Henry et al., 2001; Latorre et al., 2001; Henry, 2004). This problem continually appeared in routinely plastinated specimens (Fig. I). Therefore, it was decided to have attendees of the 12th International Congress on Plastination evaluate the surface of representative specimens from the six plastination methodologies. The results of these evaluations are presented in this paper.

Over a five-year period, various specimens from many species (human, domestic animals and exotic animals) were prepared in Knoxville, Tennessee and Murcia, Spain using classic techniques (prosection, dilation, vascular inJection, etc.) for rendering anatomical specimens suitable for plastination (Oostrom, 1987; Henry et al., 1997) and each method recorded. Fresh rather than embalmed tissue was used in preparation of most specimens. Fresh tissue was usually fixed in five to ten percent formaldehyde solution for a short time either prior to, du1ing or after prosection. A smaller number of embalmed specimens (primarily brains embalmed in I 0% formaldehyde solution) were collected and prosected. After fixation and prosection were completed, fixative was rinsed from the tissue via flowing tap water. Cool specimens were placed into either room temperature acetone (Brown et al., 2002) or cold acetone (-l5°C) (Schwab and von Hagens, 1981; von Hagens, 1985; Tiedemann and lvic-Matijas, 1988; Ripani et al., 1994; Henry et al., 1998) of at least 80% purity. Weekly changes into a higher percent acetone were performed until >99% purity was maintained. After dehydration in acetone. specimens from each type of processing were placed into plastination (vacuum) chambers containing one of the six silicone impregnation recipes for forced impregnation (von Hagens, 1985; Bickley et al., 1987; Henry and Nel, 1993).

Six recipes and techniques were carried out at various times over a period of five years in order to compare the quality of the finished plastinated specimens. as well as. provide new specimens for our collection. The six formularies were as follows:

As a group of specimens completed the plastination process, the cured and non-cured specimens were stored in appropriate cabinets and used routinely as needed for teaching, demonstration or display. The surfaces of the cured specimens, aged from four and one half years to ten days, were graded by attendees of the 12th International Congress on Plastination at Murcia, Spain. For this evaluation, the specimens were assigned and tagged with random numbers and placed on tables for voluntary participation by attendees. The evaluators were asked to examine the surface of the specimens for quality and clarity of surface detail. They were asked to disregard obvious blemished areas due to handling, shipping or abuse of the specimens. They were to record their results as follows: B - For best surface detail, G - For good surface detail and O - For okay surface detail. The results were recorded for each specimen followed by the number of responses for each category of evaluation grade.

ln addition, the authors described the surfaces of the specimens which were graded in this study to provide the reader with an idea of what the evaluators were seeing and upon which they presumably based their evaluations. The authors did not participate in the evaluation at the 12th International Congress on Plastination. The authors also described the surfaces of these specimens in their non-cured state prior to the evaluation that occurred in Spain.

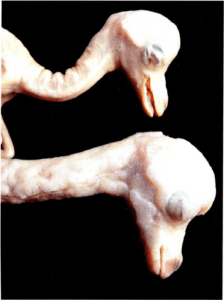

Figure l. Plastinated camel fetuses. The fetus at top was plastinated using the classic S10 process. The fetus on bottom was plastinated using the Corcoran process

Occasionally a cured specimen would weep polymer and need to be wiped and exposed to additional curing agent to complete the curing process. Specimens with no catalyst or curing agent added needed to be wiped of weeping polymer. All specimens prior to curing exhibited great surface detail. Room temperature vs. cold dehydration of specimens and room temperature impregnation vs. cold impregnation of specimens yielded no discernable difference in surface quality. Between one week and one month after exposure to catalyst, a distortion of the surface of specimens impregnated with the polymer cross-linker reaction mixture was noted on all of this type specimen. The decrease in clarity of surface detail peaked by three months post impregnation and then remained at a constant level. This decrease in clarity was due to polymer invading the surface of the specimens produced via this plastination methodology. This resulted in a dull, gritty and/or blistered appearance to the surface of these specimens. The process in which specimens were impregnated with polymer only and not exposed to any catalyst/chain extender/cross-linker was especially user friendly for hair covered specimens. Because the polymer bath contained no additives, the polymer remained fluid and drained freely from the hair and prolonged or extra manicuring was not necessary.

All classic S10 method, VisDocta TM method and North Carolina A method specimens exhibited excellent surface clarity at any time throughout the process.

The serosal surface of the bovine uterus (Figs. 2, 3) and North American opossum liver (Fig. 4) plastinated using the classic S 10 method are smooth and exhibit surface detail as is seen on fresh tissue. The margins of the liver are sharp and prominent (Fig. 4).

The VisDocta TM specimens have clear smooth margins with no excessive accumulation of polymer allowing clear visualization of all structures (Figs. 5a, 6. 7). The canine heart has a transparent epicardium such that the myocardium is visualized (Fig. 6). Brain exhibited sharp surface detail (Fig. 7).

The North Carolina processes also produced specimens with surface detail representative of fresh tissue. A feline stomach and liver display clear surface detail with sharp margins (Fig. 8). The surface detail of a porcine uterus (Fig. 9) and a canine heart (Fig. 10) is remarkable. Individual muscle fibers of the muscularis mucosa are visible through the serosa of tubular organs (Fig. 11 ).

|

|

||

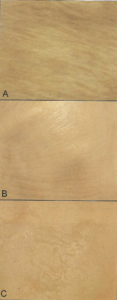

Figure 11. Serosal surface of tubular organs plastinated using the classic S10 process (A), VisDoctaTM process (B) and the Corcoran process (C).

All plastinated specimens produced with the Corcoran process exhibited altered clarity of surface detail with a slightly granular, translucent appearance after completion of polymerization (Figs. 2, 3, 5b, 6, 11). Raised. lumpy areas appeared on some specimens (Fig. 1). On transverse section, a heart is seen with subserosal accumulation of cured polymer (Fig. 12b). In many instances, surface detail is hidden by this subserosal accumulation of polymer (Figs. 6, 11 ). Nothing similar to this was found on any specimens produced using the other procedures of this study.

The Chinese process produced specimens on which surface detail appeared as it would on fresh tissue (Figs. 13. 14 ). The demarcation between the cortex and medulla on the cut surface of a feline kidney was excellent (Fig. 13). Occasionally, dry, white areas would appear on specimens produced with this method (Fig. 14). The surfaces of all specimens produced using the Chinese process remain slightly damp or oily feeling even three and one half years after impregnation.

The North Carolina BI and B2 processes produced specimens that exhibit remarkable surface detail (Figs. 15, 16, 17). One NC B1 specimen had two (2 x 3mm) raised areas of cured polymer which had oozed and not been wiped prior to curing. This common curing artifact detracted from that portion of the surface. The surface of NC B2 specimens, which received no curing. had great surface detail but remain slightly damp to touch.

Using the process in which hair covered specimens were impregnated with polymer only and not exposed to any catalyst/chain extender/cross-linker produced specimens with hair that looked and felt like it would on a living animal (Fig. 17). The drawback to this method is the specimens will remain damp for approximately one year.

Most of the finished specimens were used routinely as needed for teaching or demonstration prior to their use in this evaluation and hence some specimens exhibited small use/trauma artifacts.

The results of the evaluation by the attendees of the 12th International Congress on Plastination, Murcia, Spain are listed in table I.

| Plastination method | Tissue | # B's | #G's | #O's | |

| Classic S10 | bovine uterus | (figures 2 and 3) | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| Classic S10 | male opossum genitalia | 12 | 11 | 0 | |

| Classic S10 | porcine uterus | 13 | 10 | 0 | |

| Classic S10 | canine heart | 15 | 8 | 0 | |

| Classic S10 | opossum liver | (figure 4) | 17 | 6 | 0 |

| VisDocta | canine limb | (figure 5a) | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| VisDocta | bovine kidney | 12 | 12 | 1 | |

| VisDocta | equine brain | (figure 7) | 6 | 21 | 2 |

| VisDocta | canine heart | (figure 6) | 12 | 11 | 0 |

| VisDocta | feline stomach | 8 | 14 | 1 | |

| Corcoran | canine limb | (figure 5b) | 1 | 6 | 16 |

| Corcoran | bovine uterus | (figures 2 and 3) | 0 | 7 | 16 |

| Corcoran | male opossum genitalia | 0 | 5 | 18 | |

| Corcoran | porcine stomach | 0 | 7 | 16 | |

| Corcoran | canine brain | 0 | 6 | 17 | |

| Corcoran | canine heart | (figures 6 and 12b) | 0 | 7 | 16 |

| China | feline spleen | 3 | 12 | 8 | |

| China | feline duodenum/pancreas (figure 14) | 6 | 15 | 2 | |

| China | feline kidney | (figure 13) | 12 | 7 | 6 |

| China | feline liver | 11 | 10 | 2 | |

| North Carolina A | porcine uterus | (figure 9) | 7 | 14 | 2 |

| North Carolina A | canine heart | (figure I0) | 11 | 11 | 1 |

| North Carolina A | feline spleen | 12 | 10 | 1 | |

| North Carolina A | feline liver/stomach | (figure 8) | 4 | 17 | 2 |

| North Carolina B | feline stomach | (figure 15) | 5 | 12 | 6 |

| North Carolina B | feline kidney | 9 | 13 | 1 | |

| North Carolina B | rainbow trout | (figure 16) | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| North Carolina B | feline stomach | 12 | 10 | 1 | |

| North Carolina B | feline liver | 4 | 11 | 8 | |

All specimens produced during this project period were of good to superior quality and durable. Each of the three general types of impregnation has their own unique qualities and attributes. Since its invention, the classic SI 0 method is the most reliable method for production of high quality plastinated specimens. As well, the generic copies of the classic S IO method (VisDoctaTM and North Carolina A) provide equally as high quality plastinated specimens. Room temperature vs. cold dehydration of specimens and room temperature impregnation vs. cold impregnation of specimens yielded no discernable difference in surface quality or durability. Hence these specimens were not distinguished as a separate group for evaluation at the ISP congress.

The other two general types of plastination [impregnation reaction-mixture of polymer and cross linker (Corcoran) and polymer only in the impregnation bath (Chinese and North Carolina B)] also produced good to high quality specimens. However. the quality or specimens produced by these processes seems to be less predictable and yet all have their bright spots including a shortened impregnation time, a decreased need for freezer space for impregnation as well as the ease of polymer drainage and manicuring. The benefits in the ease of polymer drainage were most evident on hair covered specimens. The hair on specimens produced by other processes needed to be wiped excessively to remove the polymer and, even so, the hair of these cured specimens often contained some cured polymer giving the hair a matted, unnatural appearance. Currently. curing of the polymer is less predictable with these types of impregnation. If the specimens are left with a damp surface. they may not be as aesthetically pleasing to some. However, the benefit of life-like hair is great for hairy creatures.

The Chinese method recommends not to cure the impregnated specimen. Attempts to cure a few Chinese specimens by vaporizing the intended product as well as wiping it on the specimen mixed with polymer were not successful. The feline pancreas/duodenum was an example of this curing method and the surface detail was obscured in a few areas. Zheng and colleagues ( 1998a) recommend to mix old polymer with 1-5% hardener and wipe it onto the specimen su1face to produce a dry specimen. This methodology was not used in our studies as it yields specimens with a high sheen and coat of polymer on the surface.

The negative feature of the Corcoran method (polymer cross-linker impregnation reaction-mixture) is that there is poor clarity of surface detail of the impregnated specimens after curing. The appearance of the semi-translucent to opaque surface accumulation of polymer after polymerization to date has not been explained. This granular surface detracts from the beauty of the specimen and renders less prominent anatomical detail more difficult to visualize. Beyond this, nothing else has been observed that decreases the usefulness of these specimens.

The evaluation by the attendees of the 12th International Congress on Plastination tends to support the findings of the authors. However, there is a high number of "G's" (mid-grade) among all types of specimens. This is a bit worrisome, but it may be that many felt more comfortable staying near the median rather than committing to either extreme. Also, it was not known that this evaluation was for part of a publication as we did not want to bias the evaluators. Additionally. some specimens had some "wear and tear" from usage which we hoped would not be included for or against the specimen during its evaluation. If we were to do a similar evaluation again, to narrow the choices to two or to widen to five choices may have moved the "G's" to one pole or the other. However. the high number of "G's" may support the fact that surface clarity may not be a major issue for the person new to plastination or even to an established plastinator.

Bickley HC, von Hagens G, Townsend FM. 1981: An improved method for the preservation of teaching specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med 105:674-676.

Bickley HC, Donner RS, Walker AN, Jackson RL. 1987: Preservation of tissue by silicone rubber impregnation. J Int Soc Plastination 1 ( I ):30-39.

https://doi.org/10.56507/XVDP9663

Brown MA, Reed RB. Henry RW. 2002: Effects of dehydration mediums and temperature on total dehydration time and tissue shrinkage. J Int Soc Plastination 17:28-34.

https://doi.org/10.56507/XNQM4606

Glover RA, Henry RW, Wade RS. 1998: Polymer preservation technology: Poly-cur. A next generation process for biological specimen preservation. Abstract presented at The 9th International Conference on Plastination, Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, Canada, July 5-10, 1998. J Int Soc Plastination 13(2):39.

Henry RW. 1987: Plastination of an integral heart-lung specimen. J Int Soc Plastination I (2):20-24.

https://doi.org/10.56507/KQKI2988

Henry RW. 1995: Principles of plastination - dehydration of specimens. Abstract presented at The 7th International Conference on Plastination - Karl-Franzens-University, Graz, Austria. July 1994. J Int Soc Plastination 9(1):27.

Henry RW. 1998: Principles of plastination. Abstract presented at The 9th International Conference on Plastination, Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, Canada, July 5-10, 1998. J lnt Soc Plastination 13(2):27.

Henry RW. 2004: Principles of plastination. Abstract presented at The 12th International Conference on Plastination, Murcia, Spain July 11-16, 2004. J Int Soc Plastination 19:5-6.

Henry RW, Nel PPC. 1993: Forced impregnation for the standard S LO method. J Int Soc Plastination 7(1):27-31.

https://doi.org/10.56507/WUXP9436

Henry RW, Janick L, Henry CL. 1997: Specimen preparation for silicone plastination. J Int Soc Plastination 12(1):13-17.

https://doi.org/10.56507/HVSK9838

Henry RW, Brown A, Reed RB. 1998: Current topics on dehydration. Abstract presented at The 9th International Conference on Plastination, Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, Canada, July 5-10, 1998. J Int Soc Plastination 13(2):27-28.

Henry RW, Reed RB. Henry CL. 2001: "Classic" silicone processed specimens vs "new formula" silicone plastinated specimens: A two year study. Abstract presented at The 10th International Conference on Plastination, Saint-Etienne, France, July 2-7, 2000. J Int Soc Plastination 16:33.

Henry RW. Reed RB. Henry CL. 2002a: Naked silicone impregnation. Abstract presented at The 11th International Conference on Plastination, San Juan, Puerto Rico, July 14-19, 2002. J Int Soc Plastination 17:5.

Henry RW, Seamans G, Ashburn RJ. 2002b: Polymer chemistry in silicone plastination. Abstract presented at The 11th International Conference on Plastination, San Juan, Puerto Rico, July 14-19, 2002. J Int Soc Plastination 17:5-6.

Henry RW, Reed RB, Latorre R. Smodlaka H. 2004: Continued studies on impregnation with silicone polymer and no additives. Abstract presented at The 12th International Conference on Plastination, Murcia, Spain July 11-16, 2004. J Int Soc Plastination 19:47.

Holladay SD, Blaylock BL, Smith BJ. 2001: Risk factors associated with plastination: I. Chemical toxicity considerations. J Int Soc Plastination 16:9-13.

https://doi.org/10.56507/CWZW6925

Latorre R, Vaquez JM. Gil F, Ramfrez G. L6pez-Albors 0, Orenes M, Martinez-Gomariz F. Arencibia A. 2001: Teaching anatomy of the distal equine thoracic limb with plastinated slices. J lnt Soc Plastination 16:23-30.

https://doi.org/10.56507/ACRF7155

Latorre R, Vaquez JM, Gil F, Ramfrez G, L6pez-Albors 0, Ayala M, Arencibia A. 2002: Anatomy of the equine tarsus: A study by MRJ and macroscopic plastinated sections (S10 and P40). Abstract presented at The 11th International Conference on Plastination, San Juan, Puerto Rico, July 14-19, 2002. J Int Soc Plastination 17:6.

Nicaise M, Simoens P, Lauwers H. 1990: Plastination of organs: A unique technique for preparation of illustrative demonstration specimens. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr (Flemish Veterinary Journal) 59:141-146.

Oostrom K. 1987a: Fixation of tissue for plastination: general principles. J Int Soc Plastination 1 (1):2-11.

https://doi.org/10.56507/WLZH2223

Oostrom K. 1987b: Plastination of the heart. J Int Soc Plastination I (2):12-23.

https://doi.org/10.56507/YWZL8112

Raoof A. 2001: Using room-temperature plastination technique in assessing prenatal changes in the human spinal cord. J Int Soc Plastination 16:5-8.

https://doi.org/10.56507/UIHR4575

Ripani M, Bassi A, Perracchio L, Panebianco V, Perez M, Boccia ML, Marinozzi G. 1994: Monitoring and enhancement of fixation, dehydration, forced impregnation and cure in the standard S-10 technique. J lnt Soc Plastination 8( I ):3-5.

https://doi.org/10.56507/ERSG2637

Schwab K, von Hagens G. 1981: Freeze substitution of macroscopic specimens for plastination. Acta Anat I I I:139-140.

Shahar T, Pace C. 2005: Biological material preservation/plastination. Chapter 4: Chemical substances - silicone polymers. VisDocta, Tignale, Italy.

Tiedemann K, von Hagens G. 1982: The technique of heart plastination. Anat Rec. 204:295-299.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1092040315

Tiedemann K, lvic-Matijas D. 1988: Dehydration of macroscopic specimens by freeze substitution 111 acetone. J Int Soc Plastination 2(2):2-12.

https://doi.org/10.56507/SCLL2742

von Hagens G. 1979a: Impregnation of soft biological specimens with thermosetting resins and elastomers. Anat Rec 194(2):247-255.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1091940206

von Hagens G. 1979b: Emulsifying resins for plastination. Der Praparator 25(2):43-50.

von Hagens G. 1980: Animal and vegetal tissues permanently preserved by synthetic resin impregnation. US Pat No 4,205,059.

von Hagens G. 1981: Animal and vegetal tissues permanently preserved by synthetic resin impregnation. US Pat No 4,244,992.

von Hagens G. 1985: Heidelberg Plastination Folder: Collection of all technical leaflets for plastination. Anatomisches lnstitut I, Universitat, D-6900 Heidelberg, Germany.

von Hagens G, Tiedemann K, Kriz W. 1987: The current potential of plastination. Anat Embryo! 175(4):411-421.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00309677

von Hagens G, Whalley A. 2000: Anatomy art: Fascination beneath the surface. Institute for Plastination, D-69126 Heidelberg. Germany.

Weiglein A, Henry RW. 1993: Curing (hardening. polymerization) of the polymer - Biodur SI0. J Int Soc Plastination 7(1):32-35.

https://doi.org/10.56507/ABNZ7085

Weiglein AH. 1996: Preparing and using SIO and P35 brain slices. J lnt Soc Plastination 10:22-25.

https://doi.org/10.56507/IXGV4189

Zheng TZ, Weatherhead B, Gosling J. 1996: Plastination at room temperature. J Int Soc Plastination 11(1):33.

https://doi.org/10.56507/EHWO1033

Zheng TZ, Jingren L, Kerming Z. 1998a: Plastination at room temperature. J Int Soc Plastination 13(2):21-25.

https://doi.org/10.56507/YSHV9792

Zheng TZ, Xuegui Y, Jingren L, Kerming Z. 1998b: A study on the preservation of exhumed mummies by plastination. J Int Soc Plastination 13( I ):20-22.

https://doi.org/10.56507/TBQA9451

Zheng TZ, You X, Cai L, Liu J. 2001: The history of plastination in China. Abstract presented at The 10th International Conference on Plastination, Saint-Etienne, France, July 2-7, 2000. J lnt Soc Plastination 16:36-37.