Department of Anatomy, Physiological Sciences, and Radiology North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine Raleigh, NC 27606, USA

The study of the central nervous system has become a short and intense portion of the freshman anatomy course, taught concurrently with neurophysiology and neurohistology at our institution. Increased understanding of neurotransmitters, pathways, feedback loops, and interconnections make it more desirable that students be familiar with basic neuroanatomic structures. The student is hence better prepared to integrate and understand how lesions affecting these neuroanatomic structures may result in certain neurologic signs.

Currently, our neuroanatomy section is taught using whole and cross-sectioned, formalin-fixed brains and spinal cords. In past years, a great deal of time was needed to collect the brains and ensure proper and timely fixation. Also, these wet tissues are slippery to handle, gloves must be worn to protect from the fixative, and differentiation of white and grey matter can be difficult to appreciate on unstained, fixed cross- sections. Until recently, this appeared to be the best means of teaching this complicated subject. With the advent and successful incorporation of the plastination procedure in our laboratory, however, it was decided that this section of the course could more effectively be taught using plastinated specimens.

Brain; Silicone; S10

S. D. Holladay Department of Anatomy, Physiological Sciences, and Radiology North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine Raleigh, NC 27606, USA

![]()

The study of the central nervous system has become a short and intense portion of the freshman anatomy course, taught concurrently with neurophysiology and neurohistology at our institution. Increased understanding of neurotransmitters, pathways, feedback loops, and interconnections make it more desirable that students be familiar with basic neuroanatomic structures. The student is hence better prepared to integrate and understand how lesions affecting these neuroanatomic structures may result in certain neurologic signs.

Currently, our neuroanatomy section is taught using whole and cross-sectioned, formalin-fixed brains and spinal cords. In past years, a great deal of time was needed to collect the brains and ensure proper and timely fixation. Also, these wet tissues are slippery to handle, gloves must be worn to protect from the fixative, and differentiation of white and grey matter can be difficult to appreciate on unstained, fixed cross- sections. Until recently, this appeared to be the best means of teaching this complicated subject. With the advent and successful incorporation of the plastination procedure in our laboratory, however, it was decided that this section of the course could more effectively be taught using plastinated specimens.

A veterinary student was hired to assist in the collection of brains from appropriate cadavers in the College's

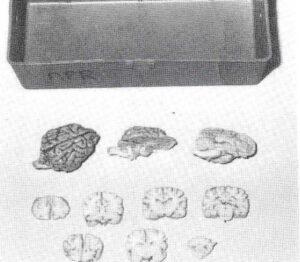

Figure 1. Student specimen box with plastinated whole dog brain, brain stem prosection, mid-sagittal section, and several representative transverse sections.

necropsy room. The student was also responsible for cleaning meninges and blood vessels from the surface of the brains. A total of 105 canine brains were fixed by immersion for in 5% formaldehyde at +5°C. Thirty of the brains were kept as whole brains, while 15 were sectioned in the median plane (producing 30 half-brains). Thirty of the brains were prepared by ipsilaterally removing half of the cerebrum and cerebellum to expose surface structures of the brain stem. The remaining 30 brains were transversely sectioned on a rotary meat slicer to produce 0.5 cm thick sections.

All of the canine brains were dehydrated by free-substitution in acetone at -20eC. The whole brains, sectioned half-brains, and brain-stem prosections were plastinated using silicone (S-10) resins. The transverse sections were plastinated between plates of glass with polyester (P-35) resins. The plastinated brains were then divided into 30 plastic toolboxes so that each box contained one whole canine brain, one mid- sagittally sectioned brain, one brain- stem prosection, and one transversely sectioned brain (Fig. 1). Beginning the fall semester 1990, one brain box will be assigned to each group of three veterinary students, in similar manner to that now used for student- study bone boxes. Twenty-four boxes will be dispersed among 72 students, leaving six sets to serve as "spare parts" and replacement material.

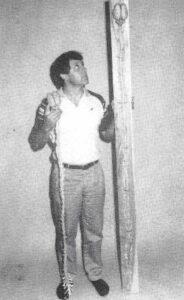

Figure 2. Plastinated horse brain and spinal cord (mounted) and pony brain and spinal cord with dura, nerve roots, and ganglia.

In addition to the canine brain study boxes, other central nervous system specimens were plastinated to further enhance teaching of the neuroanatomy section. These included brain and spinal cord from an adult horse (7 feet long after plastination) including dura (opened), nerve roots, and ganglia (Fig. 2); a series of brains from human, horse, cow, goat, sheep, pig, dog, cat, rabbit, turkey, and chicken; decorticated brains of several species; and the brain and spinal cord were exposed (including dorsal root ganglia, brachial plexus, and lumbosacral plexus nerves) in situ in a 40-pound dog and the whole specimen plastinated.

We have observed that students will use plastinated brains more readily than formalin-fixed brains. They are more pleasant to touch, do not drip on the student's text or notes, and do not cause tearing, respiratory irritation, and topical allergic reactions that have been a problem in anatomy laboratories in the past. Additional concerns now over the carcinogenic potential of formaldehyde and determining "safe" levels are making it advantageous to remove such fumes from the student laboratory as much as possible. Also, our experience is that these specimens will last many years, reducing the need to find so many canine cadavers suitable for collection. This is becoming more important in light of often dwindling availability of cadavers and increased cadaver costs.

This project was funded by an education grant from the Merck Company Foundation.

none